This video provides a virtual introduction to the Grand Canyon. Don't worry about learning all the names of the features it describes; just use the video to get a sense of the scale and beauty of the Grand Canyon. Credit: NASA, US National Park Service, US Geological Survey.

Watch this PBS video for a brief overview of how the Grand Canyon was formed.

CHAPTER INTRODUCTION

The Grand Canyon is a very famous place. But if you look carefully at the photo of it above, or watch the accompanying videos, you’ll see that the Grand Canyon also gives us a picture of time. Its layers record hundreds of millions of years of Earth’s history, holding clues not just to how the canyon itself formed, but to the forces that gradually transform our planet and to the conditions that have existed at different times in our planet’s past.

In the prior chapter (Chapter 4), you developed a “big picture” view of our planet, including learning about how it formed and what it looks like today. In this chapter, we’ll begin to fill in the details. We’ll explore how scientists have learned to read the clues found in rocks and fossils at places like the Grand Canyon, we’ll study the processes that shape our planet’s surface, and we’ll use these ideas to put together a brief history of how the Earth has changed through time.

Note that in doing this, we will be focusing primarily on the geosphere, since we are examining the changes we see in Earth’s solid surface. Of course, we’ll also see that the geosphere is influenced by Earth’s other systems as well. The Grand Canyon provides a great example:

- The rock layers themselves are part of the geosphere.

- The layers are exposed because they were cut by a river, which is part of the hydrosphere.

- The river could not exist without the atmospheric pressure and the water cycle made possible by the atmosphere.

- And we learn a lot about the rock layers because they contain the fossil remnants of once-living organisms, which connects them to the biosphere.

Journal Entry

Thinking about the Grand Canyon

If you haven’t already, watch the two short videos that accompany Figure 5–1 above of the Grand Canyon. After you have watched them, write a short entry in your journal in which you briefly describe at least three facts you learned about the Grand Canyon that you find particularly interesting, and what you found interesting about each of them.

This journal entry is intended simply to make sure students watch the two short videos, which will be useful to them in setting context for the rest of the chapter.

Group Discussion

Geological Detective Work

Working in small groups or as a class, do your best to answer the following questions. Don’t worry if you don’t know all the answers; you’ll learn the correct answers later in this chapter.

- Look at the many layers of rock visible in the Grand Canyon photo. How can you tell which rock layers are the youngest, and which are the oldest?

- Many of the fossils found in the rock layers of the Grand Canyon are of sea shells, fish, or other organisms that live in the sea. What does that tell you?

- How do you think the rock layers formed? Hint: Look back at Figure 4.38 for ideas.

- The top of the Grand Canyon lies more than 2,000 meters above sea level. Building on your answers to the prior questions, what does this tell you has happened to the land around the Grand Canyon after the rock layers formed?

- The Colorado River runs through the bottom of the Grand Canyon. How can you tell that the river carved the canyon, as opposed to the river having come first and then the walls building up above it?

- We briefly introduced the concept of plate tectonics in Chapter 4. Can you think of a way that two plates coming together might have led to the Grand Canyon’s high elevation?

This discussion should help students think ahead to some of the ideas that we will discuss in this chapter. As it notes, you should not expect students to know all the answers already, but only to think about them as “geological detectives” trying to make sense of the given facts.

- The youngest layers are at the top and the oldest at the bottom. As we’ll discuss in Section 5.1, this is a general feature of how sediments are deposited in layers.

- The marine fossils tell us that the sediments and fossils were deposited at a time when this region lay beneath the sea.

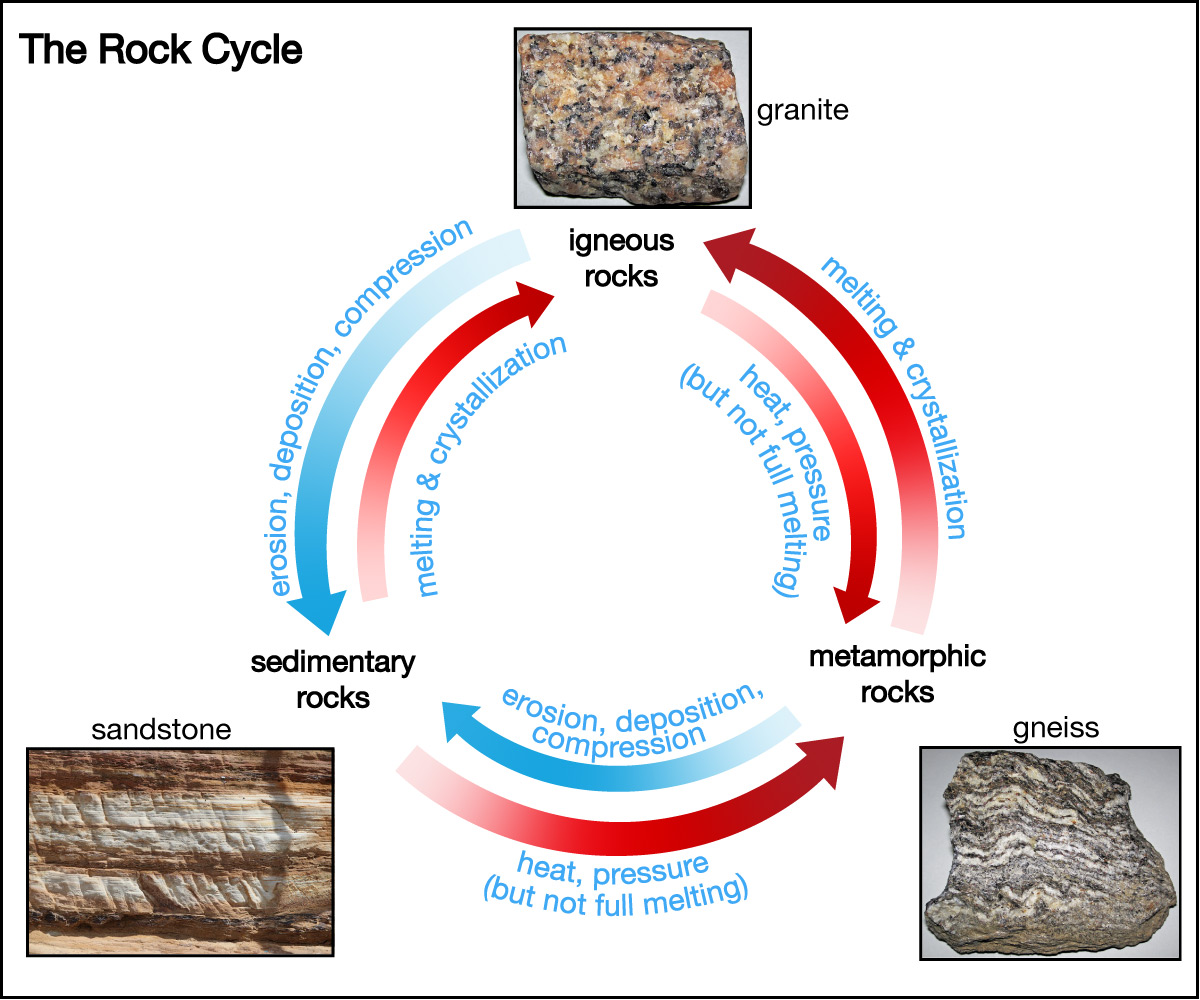

- The blue arrows in Figure 4.38 show that sedimentary rock formation requires erosion, deposition, and compression. This, combined with the idea from question 2 that the layers were once at a sea bottom, may help students realize that the layers formed as rock sediments were weathered/eroded away, carried downstream by streams or rivers, deposited in a sea, and then compressed into solid rock.

- Since this region lay beneath the sea when the sediments were deposited, it must have been uplifted to its current elevation.

- Building on the answers above, the sediments had to pile up at a time when the layers were under a sea. They could not have piled up on either side of a river, since there are no rivers at the bottom of the sea. The river must have cut through them later, after the layers were uplifted above sea level.

- This question is challenging because we have not given a direct example previously, but is related to the association of trenches with island arcs and mountain ranges. As noted briefly in Chapter 4, the subduction of one plate under another can pull the lower plate down to create an ocean trench while pushing the upper plate upward, leading to a mountain range or island arc. More generally, subduction tends to cause uplift of the upper plate. When it proceeds in a fairly smooth fashion, it can simply lift up existing rock layers without greatly disturbing them, as appears to have happened with the Grand Canyon.

Optional Video

Grand Canyon in Greater Depth

The videos above gave you a brief introduction to the Grand Canyon, but they may leave you wondering more about this remarkable place. Two particularly good documentaries about the geological history of the Grand Canyon are: (1) National Geographic’s “Naked Science: Grand Canyon,” which you can view here; and (2) the Grand Canyon episode of the series “How the Earth was Made,” available here on Amazon. After watching the video, hold a brief class discussion about how scientists use evidence and reasoning in their work to learn about the history of the Grand Canyon.

If you can spare the class time, you might wish to watch one of the two videos listed in this activity with your students. Both are quite well done (except as noted in the bullets below), and will provide your students with a nice introduction to how geology works, which can be helpful in providing context for the rest of this chapter. For the class discussion: Students by now should be quite familiar with the “evidence and reasoning” ideas, so this is a great chance for them to turn it around and explain how what they saw of the scientific “detective work” in the video fits that motif.

Notes on “How the Earth was Made”: We really like the approach this series takes in putting together clues to show how scientists use evidence and reasoning to reach conclusions. There are, however, a few inaccuracies you should be aware of and discuss with students:

- The series takes some dramatic license to make the process from evidence to conclusion seem more linear than it really is. This is OK – just be sure your students understand that the series is using hindsight to reconstruct more complex scientific detective stories.

- The series consistently uses the term “theory” where it should really be saying “hypothesis.” While this is common in everyday speech, so perhaps justified in a dramatic documentary, it may confuse students who are thinking about its scientific definition, as discussed in Chapter 3.

- In the episode on the Grand Canyon, the series does a good job of discussing the spillover hypothesis, even showing a large physical model created to test it. Be aware, however, that this hypothesis remains more controversial than the show implies, and is still just one of several competing models concerning the origin of the Colorado river. Note: If you watch additional episodes, this is a general characteristic of the series, in that it often implies things have been “proved” when there is still some legitimate scientific debate about them.

- Although it doesn’t come up in this particular episode, later episodes of this series mistakenly imply that the mantle is molten, when in fact (as discussed in Chapter 4), the mantle is solid except for relatively small pockets of magma.