The historical discussion in this section is not directly required in the NGSS middle school standards. However, it provides crucial context for understanding the nature of modern science (as discussed in Section 3.3), so we highly recommend that you spend at least a little bit of time on it. For your own background, and to show to students if you have time, we also highly recommend watching Episode 3 (“Harmony of the Worlds”) of Carl Sagan’s original Cosmos television series.

Imagine having been born in the year 1543. The idea of Earth as the center of the universe was still generally accepted, which means we did not yet know that Earth was a planet. But a change was beginning, and by the time you reached old age, you would have lived to see human thinking go through perhaps the greatest change that has ever occurred in humanity’s perspective on the universe. In essence, you would have lived through the discovery of planet Earth.

Section Learning Goals

By the end of this section, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- How did the idea of Earth as a planet gain favor?

- How did Galileo seal the case for Earth as a planet?

Before you continue, take a few minutes to discuss the above Learning Goal questions in small groups or as a class. For example, you might discuss what (if anything) you already know about the answers to these questions; what you think you’ll need to learn in order to be able to answer the questions; and whether there are any aspects of the questions, or other related questions, that you are particularly interested in.

Activity

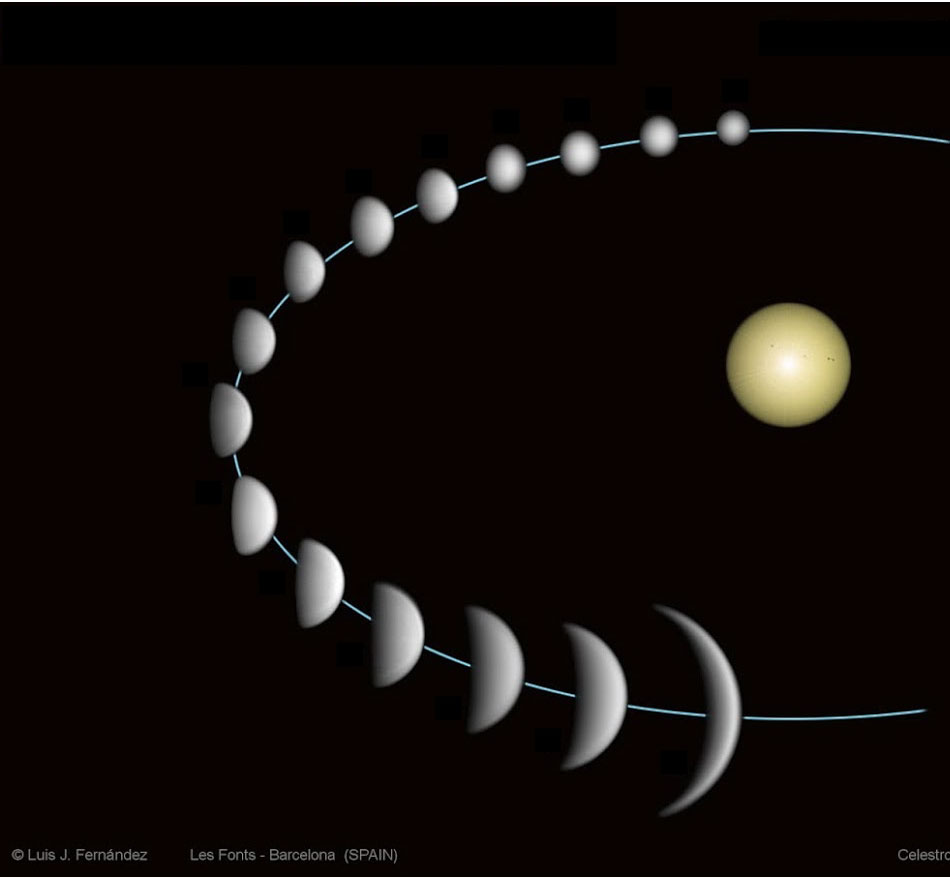

Phases of Venus

In this activity, you will explain the phases of Venus as illustrated in Figure 3.5. Set up a light source (such as a lamp with a bright bulb) on a table and have one student hold a white ball to represent Venus. Other students should stand farther from the table to represent Earth. Be sure that the room is dark enough so that as the first student (holding Venus) moves to different positions, it is possible for the others to see the ball (Venus) going through phases (much as you demonstrated phases of the Moon in chapter 2). Then do the following.

- Observe the phases that you see as the student holding Venus (the ball) walks around the Sun (on the table). Do you see the same set of phases as shown in Figure 3.5?

- Can you also use this demonstration to explain why Venus’s size seems to change at different points in its orbit (as you can see in Figure 3.5)?

- Now, try having the student holding Venus move around you (Earth) instead of the Sun. Is there any possible way to still get the changes in phase and size that we see in Figure 3.5? Based on your results, use evidence and reasoning to support the following claim: Observations of Venus’s phases (as shown in Figure 3.5) prove that Venus orbits the Sun and not Earth.

- Now that you’ve seen that Venus’s phases prove that Venus orbits the Sun, can you explain why the ancient Greeks didn’t recognize this fact?

We start this section with this activity so that students will understand one of the key pieces of evidence that helped establish that Earth is a planet orbiting the Sun. This should provide useful context as we then go back in time to see why it took so long for this fact to become clear. In terms of the activity itself, the key point is that the phases of Venus occur for the same basic reason as phases of the Moon: the side of Venus that is facing the Sun is completely sunlit (day) and the other side is dark (night), and the phase we observe depends on how much of the day side and how much of the night side we are viewing at each position. This demonstration should help students see how this leads to the observations that are shown in Figure 3.5. Notes on the specific questions

- (1) If the demonstration is successful, students should be able to clearly see the ball going through phases that match what is shown in Figure 3.5. Note: if you are unable to set up a successful demonstration, you may still be able to do this activity by diagramming it on a chalk board or white board.

- (2) Venus looks bigger when it is closer to us (for example, when it is on the same side of the Sun as Earth) and smaller when it is farther away (closer to the opposite side of the Sun). Again, this should be clear if the demonstration is successful.

- (3) No matter what students try, they will find that they cannot reproduce the observed pattern unless Venus is orbiting the Sun; the same sequence of phases cannot be observed with Venus orbiting Earth. Therefore, the observed pattern in Figure 3.5 proves that Venus orbits the Sun.

- (4) This one is easy: The telescope had not yet been invented, and the phases are not noticeable to the naked eye.