Figure/Video 5.1–1 – Much of what we know about the Earth comes from careful study of rocks and fossils, our topic in this section.

Note: Starting in this chapter, we are using a different scheme for figure numbering, with the numbering restarting in each section and subsection. For example, Figure 5.1–1 is the first figure in Section 5.1, and Figure 5.2.1–3 is the third figure in Section 5.2.1. We’ve done this so that you can more easily find figures based on their locations in the text.

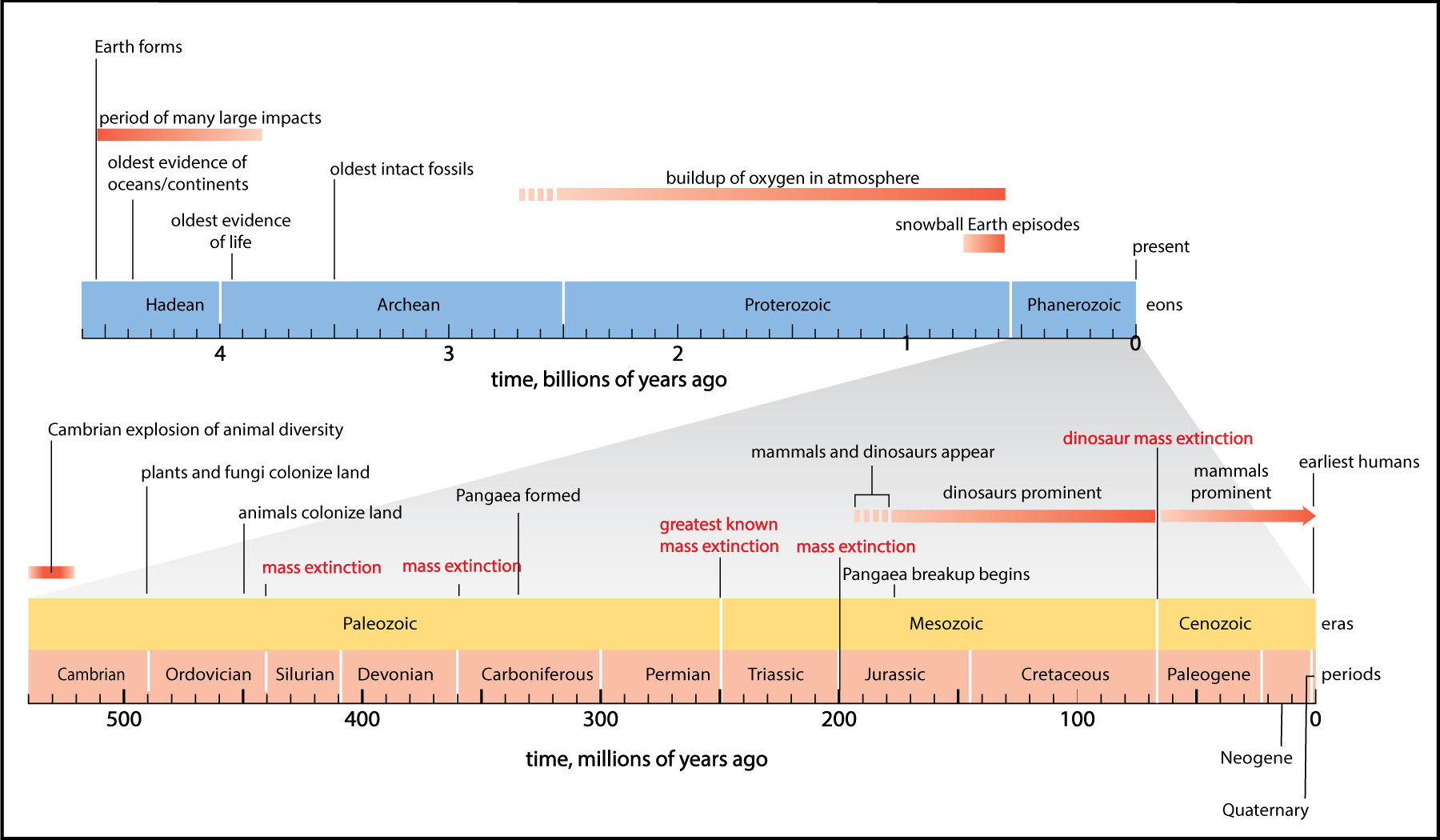

Rocks are everywhere around us. After all, the ground we walk on is the rocky surface of our planet. Most of the time, we pay little attention to all these rocks. However, geologists have discovered that if you learn how to read the clues they hold, rocks can tell us a lot. Indeed, the geological time scale , which we’ve briefly explored already (see Figure 4.24) is put together through this careful reading of rocks and the associated fossils that they hold.

In essence, learning to read the clues in rocks is like learning how to read in general. When you were very young, the letters on the pages of a book did not have any meaning for you. The same is probably still true for you if you look at a book written in a language that uses a different alphabet, such as Greek or Arabic or Hebrew or Chinese. But once you learn how to read the letters, you can then begin to see how they are put together to form words, sentences, paragraphs, and stories.

It takes many years of training for geologists to learn how to read the stories written in rocks, but the basic ideas are ones you can begin to understand right now. In this section, we’ll explore these ideas, which will help you understand how geologists have gradually learned about the history of our planet.

Section Learning Goals

By the end of this section, you should be able to give general answers to the following questions:

- How do rocks form?

- What are fossils?

- How do we learn the ages of rocks and fossils?

Before you continue, take a few minutes to discuss the above Learning Goal questions in small groups or as a class. For example, you might discuss what (if anything) you already know about the answers to these questions; what you think you’ll need to learn in order to be able to answer the questions; and whether there are any aspects of the questions, or other related questions, that you are particularly interested in.

Journal Entry

Rock Photo Journal

For this journal entry, find at least 3 interesting rock formations that are near your home or school. (If you live in a city, parks are a great place to look.) Take a photo of each one and put it into your journal. Be sure you describe where each of your rock formations is located, so that you can find them again later. Along with your photos, write a paragraph about each formation in which you describe any notable features that might give clues to its history. For example, notice whether it seems to contain any layering of the type seen in the Grand Canyon, or whether it looks to be of a single rock type or mixed types, and so on. If the formation has a name, or is located in a prominent place, see if you can find any information about its geological history on the web.

This journal entry asks students to take some photos and put them into the journal, writing a bit about each one. A few notes:

- The main goal of this activity is simply to get students paying attention to details of rocks that they might have ignored in the past. We don’t expect them to be able to identify rock types or the geological history of their formations; we only want them to think about the fact that this could be done in principle, if they had the necessary background knowledge of geology.

- If you have a nearby park, or other nearby rock formations of interest, you could have students take a field trip to it for the purpose of taking their photos.

- Further to the above, you might check whether your local region has any rock formations of particular geological interest. If so, steer students toward photos of those.