On any given night, the planets stay approximately fixed in position relative to the stars in our sky, which means they rise and set just like stars. So how can you tell what’s a planet and what’s a star?

Planets as Wanderers

Sometimes it’s easy to recognize a planet, at least if you know a little about the planets. For example, Venus and Jupiter often shine more brightly than any star in the night sky, so they are easy to find at the times when they are visible. But the real trick to spotting planets was discovered thousands of years ago: If you watch for many nights, the planets are the objects that we see gradually wandering through the constellations. In other words, stars stay fixed in the patterns of the constellations, while planets gradually move relative to the stars.

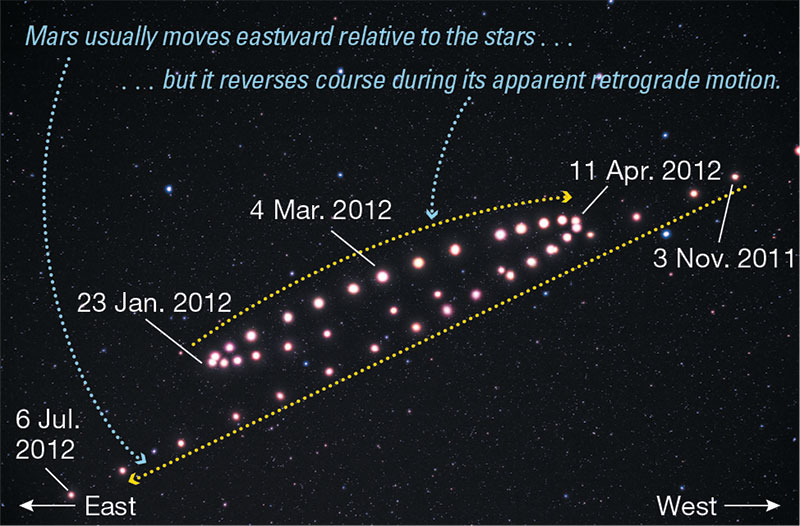

Figure 2.33 (repeated below) shows this “wandering” for Mars over a period of many months. In fact, the word planet comes from an ancient Greek word meaning “wanderer.” Keep in mind that you won’t see a planet like Mars wandering in a single night, but as weeks and months go by you’ll see that it moves from one constellation to another.

Ancient people didn’t know why the planets wander, and their strange motions — such as the looping motion of Mars shown in Figure 2.33 — made planets seem mysterious and powerful, which is probably why the planets were given the names of ancient gods. Today, we know that the real reason the planets wander in our sky is because both we (Earth) and they are orbiting the Sun together. This also explains why the planets wander only through the constellations of the zodiac (the same constellations through which the Sun appears to pass each year): Because all planets orbit the Sun in nearly the same plane, they can never venture far from the Sun’s path through the sky (the ecliptic).

Key Concepts: Planets in the Night Sky

Unless you know that you are looking at a planet, there is no obvious way to distinguish a planet from a star during a single night of observing. This is because, over a single night, a planet will appear to stay in the same position among the stars, rising and setting just like the stars around it. The way you can identify planets is by observing over a period of many nights (sometimes requiring weeks or months), which will allow you see that the planets gradually “wander” among the constellations of the zodiac.

Journal Entry

Tonight’s Planets

Go to the web page www.timeanddate.com/astronomy/night/ to find out which planets will be visible in your sky tonight. List these planets in your journal, along with notes about when and where you can try to see them. Then, if it’s clear and not too late at night, go out and try to see the planets. Afterward, add notes to your journal about whether you successfully saw the planets.

Teacher Notes: The goal for this journal entry is to get students to think about how the seasons affect them personally before you have students discuss them as a group. The list will vary both with your location and with students’ individual backgrounds.

The Days of the Week

If you think back, you’ll realize that at this point you know the astronomical origins of a day (Earth’s daily rotation), a month (the Moon’s cycle of phases), and a year (Earth’s orbit around the Sun). So you might be wondering: Does the week have an astronomical connection? The answer is yes, though in a way that surprises most people.

To understand the origin of our week, you have to think about the way ancient people thought about planets. Remember that, by its ancient definition, a planet was an object that wanders among the constellations in the sky. Of the eight planets we know today in our solar system, ancient people recognized only five: Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. They did not know about Uranus or Neptune, because those are too dim to notice without a telescope. They also did not count Earth as a planet, because the fact that we live on Earth means we don’t see it wandering through our sky.

Activity

Quick Discussion — Ancient Planets

Before you read on… We’ve just stated that of the 8 planets we know today, ancient people recognized only five: Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. But were there any other objects in the sky that would have met their definition of a planet as an object that wanders among the constellations? Discuss with your classmates and see if you can come up with an answer.

Teacher Notes: This “quick discussion” is only meant to take a couple of minutes, to see if students realize why the Sun and Moon were considered “planets” by the ancient definition.

OK, now that you’ve concluded the above discussion… Perhaps you realized that the Sun and Moon also “wander” among the constellations, which means they also fit the ancient definition of planets. Adding them to the other five, this means that ancient people recognized a total of 7 planets — and that is the reason that we have 7 days in a week! In fact, the 7 days are each named for one of those “planets”:

- Sunday, Monday (“Moonday”), and Saturday (“Saturnday”) are fairly obvious in English.

- The other four days are much less obvious in English, but easy to see in many other languages. For example, if, you know Spanish:

- Tuesday is martes, which makes it “Mars day”

- Wednesday is miércoles, which makes it “Mercury day”

- Thursday is jueves, which makes it “Jupiter day”

- also note that if you like Marvel movies, you are familiar with Thor, who is the Norse god equivalent of Jupiter – making it very easy to see that “Thorsday” in English corresponds to Jupiter’s day in Spanish.

- Friday is viernes, making it “Venus Day.”

Activity

Group Discussion — 8 Days a Week

The planet Uranus is actually faintly visible to the naked eye, but it is so dim and moves so slowly through the constellations (because it is so far from the Sun) that it was not recognized as a planet in ancient times. But imagine that Uranus had been much brighter, so that our ancestors did recognize it as a planet. Do you think we would then have (as in the famous Beatles song) “8 days a week” instead of 7? Discuss your opinion with your classmates.

Teacher Notes: There is no definitive answer to this next discussion question, since there is no way to go back and check the actual effects of a hypothetical like this. Nevertheless, it seems logical to assume that a brighter Uranus would indeed have led us to have 8 days rather than 7 days in a week. This makes it a fun discussion topic for students.

- One issue that some students may raise is the fact that we usually associate our 7-day weeks with the time between the major phases (new, first-quarter, full, third-quarter) of the Moon. However, 8-day weeks are only marginally worse for this. Remember that the actual cycle of phases is about 29 ½ days. This is 1 ½ days longer than four 7-day weeks, and 2 ½ day shorter than four 8-day weeks.