Energy Formulas and Equations

In high school and college science and engineering courses, you’ll often need to calculate energy values. Fortunately, many forms of energy can be calculated with simple formulas. You’ve already seen one example of this: The earlier box on E = mc2 showed you how to calculate the mass-energy of an object in joules. Here, we’ll look at three other simple examples:

Kinetic energy:

The formula for the kinetic energy of a moving object is

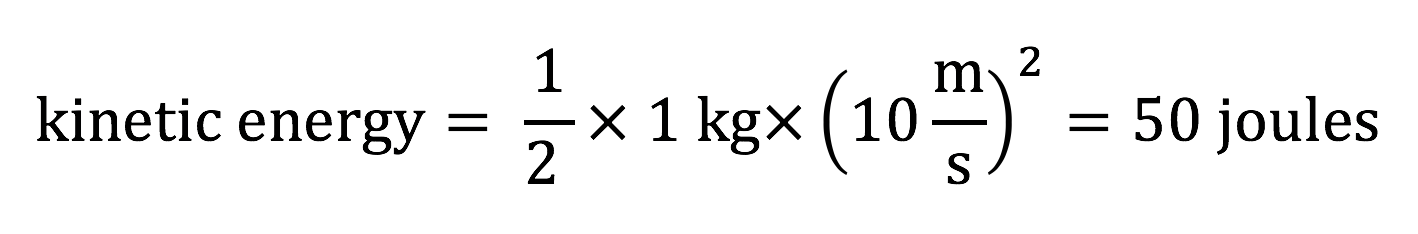

which gives an answer in joules if you enter the object’s mass m in kilograms and its speed (velocity) v in meters per second. For example, if a 1 kilogram mass is moving at a speed of 10 meters per second, then its kinetic energy is:

Note: If you follow the units in the above calculation, you can see joules must be equivalent to units of (kg m2 )/ s2. In other words, 1 joule is the same as 1 (kg m2 )/ s2. We state the final answer in “joules” because those are the standard units for energy, and it is easy to say “joules” than to say “kilogram-meters-squared, per second squared.”

Gravitational potential energy:

The formula for the gravitational potential energy of an object near the surface of the Earth is:

where m is the mass of the object, g is the acceleration of gravity, and h is the object’s height above whatever it might potentially hit if it falls (which might be the ground, or the floor, or a table, or something else). Again, this formula will give an answer in joules if you measure the mass in kilograms, the acceleration of gravity in meters per second squared (recall that on Earth’s surface, g = 9.8 m/s2), and the height in meters.

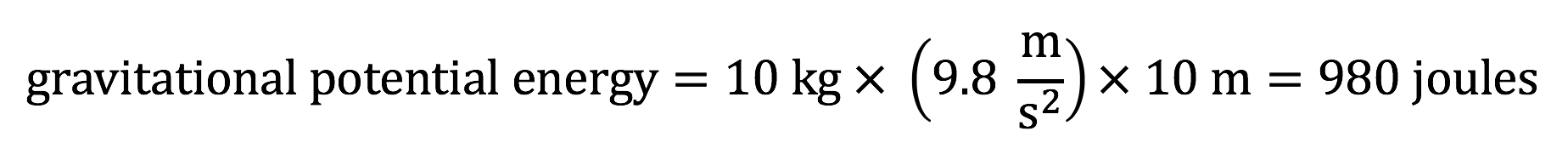

As an example, consider a 10-kilogram boulder perched at the top of a cliff that is 10 meters high. The gravitational potential energy of this boulder is:

Note: Again, if you follow the units in the above calculation, you can see joules are equivalent to units of (kg m2 )/ s2.

Thermal energy changes

With thermal energy (which, again, is the combined kinetic energy of all the particles in a substance), we are generally interested in the amount of energy needed to heat or cool a substance by a particular amount. This depends on something usually called the “specific heat” of a substance, which you can look up. For example, the specific heat of water is about 4,180 joules per kilogram per degree Celsius, which means it takes 4,180 joules of energy to raise the temperature of 1 kilogram of water by 1°C. This leads to a simple formula:

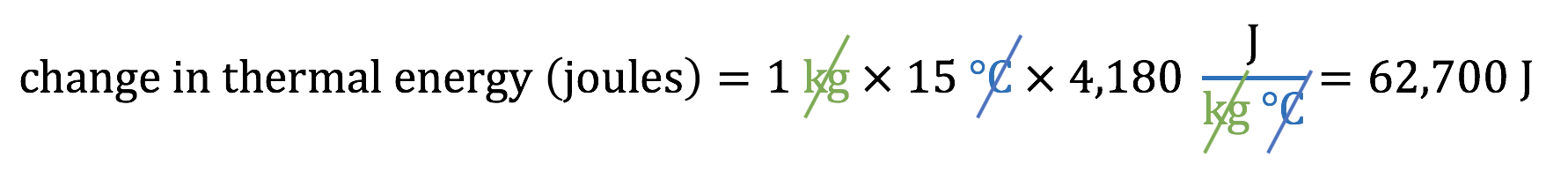

For example, suppose you have a pot with 1 liter of water, which weighs about 1 kilogram, and you want to raise its temperature from 25°C to 40°C, which is a 15°C increase. Then the amount of energy you’ll need is:

That is, you’d need to add about 62,700 joules of energy to the pot to raise the water temperature by 15°C.