As we’ve discussed, we already have technologies (through some combination of efficiency, renewables, and existing nuclear fission power) that could in principle allow us to eliminate our greenhouse gas emissions while still having the energy to meet all our needs, and we will have technologies that can do much more in the future. So you might wonder, why haven’t we already solved the problems of global warming?

This question gets to the heart of the search to solutions for global warming. Science tells us that the problem is real, and engineering tells us that it is solvable. But actually implementing a solution is much more complex, because it requires actions, and the decision to act on an issue like this one involves human psychology, economics, and politics (Figure 7.3.3–1).

This is a science course, so we won’t spend a lot of time on these “other” issues. However, because the science tells us that the problem is extremely consequential to all of our futures, we cannot simply ignore those issues either. In this section, we’ll briefly address some of the economic issues and some of the proposed political solutions.

Discussion

Margaret Thatcher on Global Warming, Part 2

Look again at the 1989 quote about global warming from conservative British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher that we discussed in Part 1 of this discussion. Later in the same speech from which that quote is taken, she urged strong, rapid, and international action to alleviate the threat of global warming.

- Imagine that the world had acted as she urged at that time, moving rapidly to replace fossil fuel sources. Discuss how you think today’s world would be different if we had listened to her. Discuss not only energy, but how you think the world would be different in terms of prosperity, politics, human health, and more.

- Given that the world did not follow Thatcher’s advice at the time, discuss what lessons we can still learn from her about what we should do today. How might the phrase “better late than never” apply?

- As you are probably aware, the topic of global warming has often become politicized in the decades since Thatcher’s speech. In particular, many people have allowed their view even of the basic science to be colored by their personal political beliefs. (Note that this is true across the political spectrum, not only on one side or the other.) Briefly discuss how Thatcher’s speech shows that the issue should be considered one of science, not politics. Then discuss how you think the issue could be de-politicized, so that everyone can agree on the importance of coming to a solution, even if different people favor different solutions.

This discussion returns to Thatcher’s quote as a way of setting the stage for thinking about pathways to solutions for global warming. A few notes:

- (1) This first question is designed to get students thinking about how the world would be different if we had acted much earlier on global warming. The most obvious “answer” is that if we had dealt with global warming more seriously back in 1989, then we might no longer be facing it as a major problem today. Students may also come up with many other ways in which the world might have been different. For example, early action might have meant that the topic would not have become politicized, so we might have less divisive politics today. Similarly, since moving away from fossil fuels would also have reduced air and water pollution, overall human health might be much better today.

Be careful to steer this discussion in a way that inspires students to think about the benefits that we’ll ultimately see from a solution, rather than getting discouraged about the fact that we don’t already have these benefits today. - (2) We hope this question will inspire students to realize that “better late than never” clearly applies in this context, so that they are ready to think about exactly what actions we might take.

- (3) Students will almost certainly be aware of the ways in which the issue has been politicized, so this is your chance to let them discuss what they hear around them. We hope that Margaret Thatcher’s stature as both a global leader and a strong conservative will convince students that while the choice of solution may be political, the understanding of the problem is not.

- Note: If you have the time, it is worth showing at least parts of Thatcher’s speech in the linked video, or reading aloud from the transcript that accompanies it. She made numerous statements that will show the depth of her concern for the environment overall, which can be quite inspirational and further demonstrate that these should be nonpolitical issues.

Energy Economics

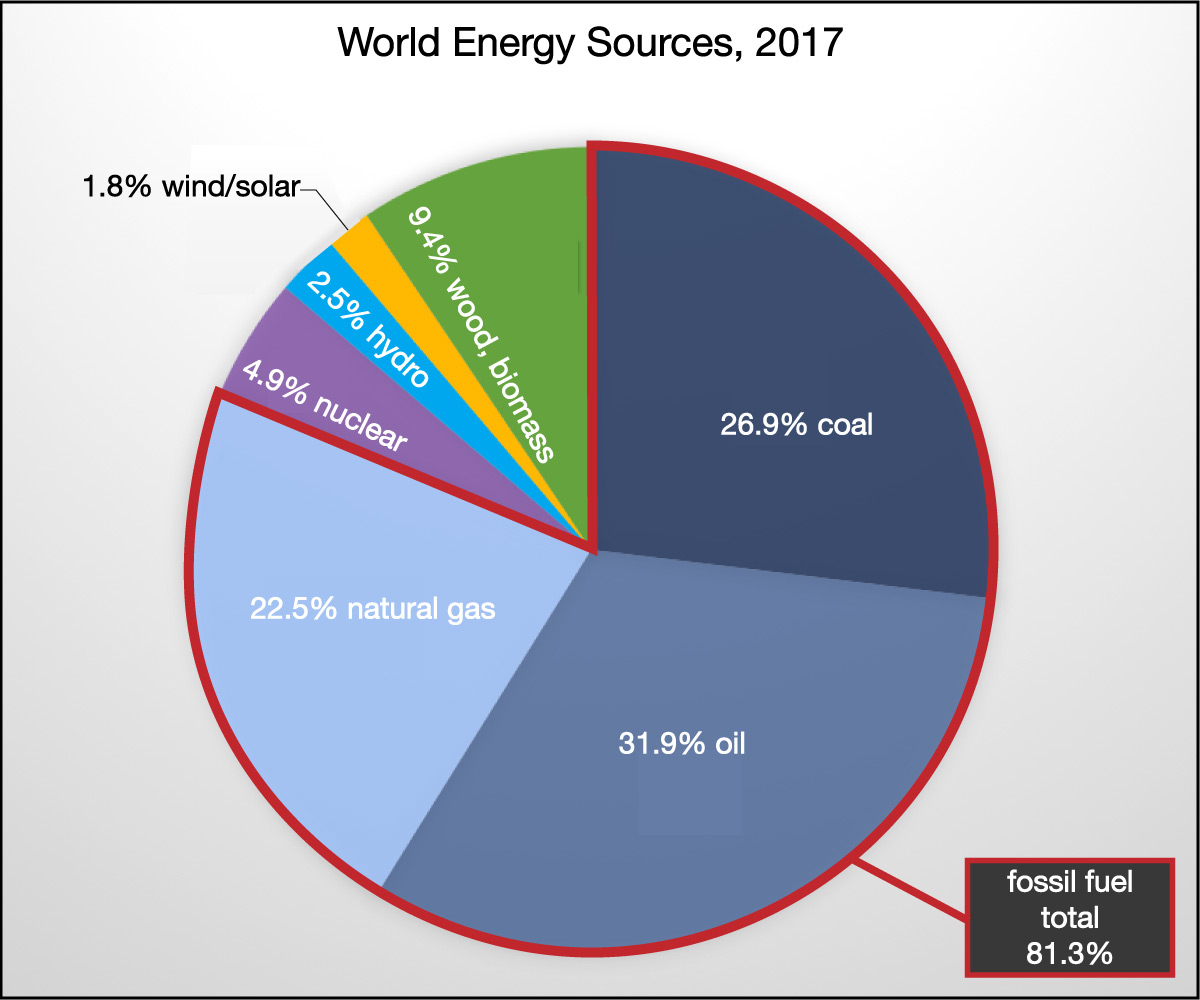

Perhaps the biggest single reason why fossil fuels continue to dominate the world’s energy supply (see Figure 7.3.1–1) is pricing: If you are looking for a steady (not intermittent) source of energy, fossil fuels are still generally the cheapest option at the time of purchase. However, the key words here are “at the time of purchase.” The reason is that the purchase price does not include what economists call externalities , which are costs associated with the energy that are not paid at the time of purchase.

As an example, imagine that you operate a coal-fired power plant. Unless a government makes you pay more, the only costs you will pay to buy coal are those associated with mining the coal and shipping it to your power plant. But as you know, the use of the coal is also associated with health costs to due air and water pollution, environmental costs of damage from coal mining, and costs from the consequences of global warming. Because none of these “other” costs are included in the price of the coal, they count as externalities. Note, however, that these external costs are just as real: Someone is paying these costs, just not the person who buys the coal. For example, the health costs of the air and water pollution are paid through doctor and hospital bills, which means they become built into everyone’s health insurance payments.

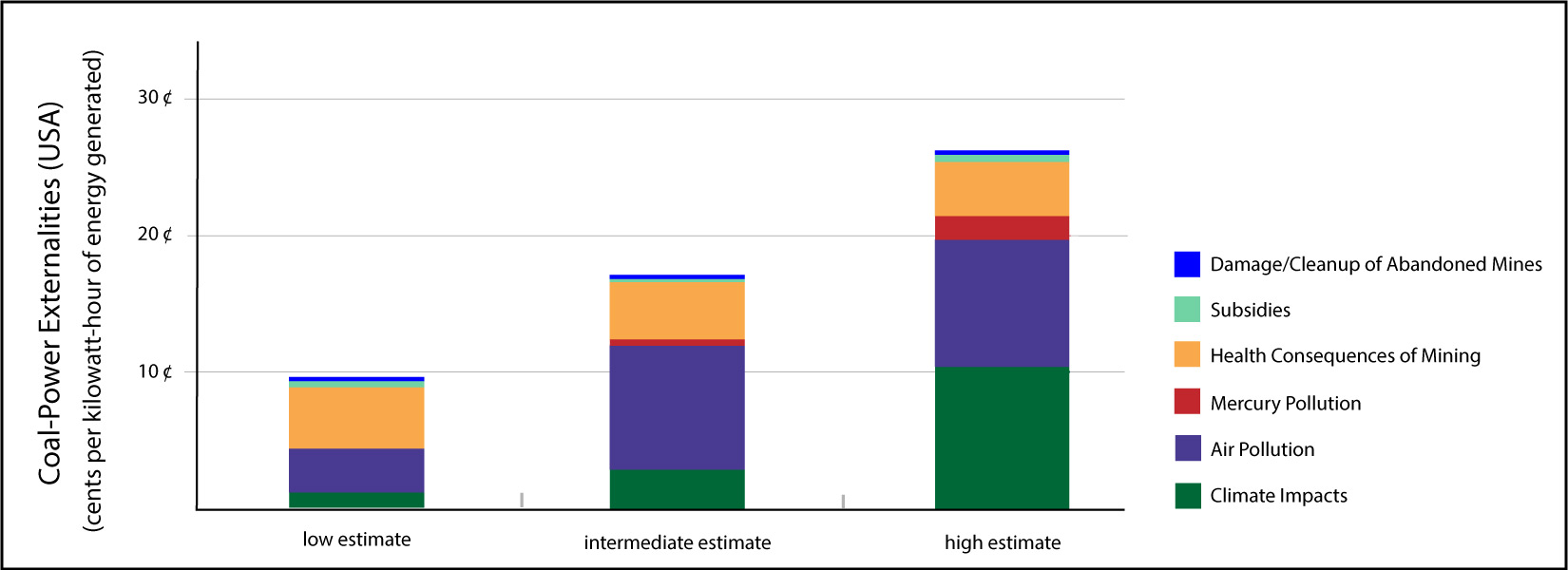

It’s not easy to identify and quantify all the externalities of fossil fuels. As a result, there is great debate among economists about exactly how much they amount to . Nevertheless, there is near-universal agreement that they are quite large. Figure 7.3.3-2 shows low, intermediate, and high estimates for the externalities associated with coal power in the United States. Try the questions that follow the figure to make sure you understand the context.

Discuss the following questions based on Figure 7.3.3-2 with a classmate. Then click to open the answers to see if they agree with what you came up with.

- The average price of coal-powered electricity in the United States is roughly 12 cents per kilowatt-hour. Suppose you home uses 1,000 kilowatt-hours of electricity in a month. How much do you pay for that electricity?

Using the abbreviation kWh for kilowatt-hours, the amount you pay for the electricity is $0.12/kWh × 1,000 kWh = $120.

- Again assume that your home uses 1,000 kilowatt-hours of coal-powered electricity in a month. Using the low estimate shown in Figure 7.3.3–2, what is the approximate cost of the externalities associated with this energy use?

The low estimate for the costs of the externalities is about 10 cents per kilowatt-hour. Therefore, for 1,000 kilowatt-hours of electricity, the externalities amount to about $0.10/kWh × 1,000 kWh = $100.

- Who pays each of the costs that you found in questions 1 and 2? Explain clearly.

The $120 from question 1 is the actual price you are charged for the electricity, so that means it is paid by you (or your family) when you receive your bill from the electric company. The $100 in externalities from question 2 is not included in your electric bill. This means it is paid by society as a whole, through such things as costs of health care, costs associated with damages from global warming, taxes, and so on.

- Suppose that the government decided that the people who use the electricity should pay the costs of the externalities, and therefore implemented a “coal-powered electricity tax” to charge this amount. Again assuming the low estimate from Figure 7.3.3–2, how would that change the price that you pay for your electricity, per kilowatt-hour?

The tax would need to equal the approximately 10 cent per kilowatt-hour cost of the externalities. Therefore, your price would rise from 12 cents to 22 cents per kilowatt-hour. Note that this almost doubles your price.

- How would your answer to question 4 change if you used either the intermediate or high estimates shown in Figure 7.3.3–2?

The intermediate estimate is about 18 cents per kilowatt-hour, which means your price would rise from its original 12 cents to 30 cents per kilowatt-hour. In other words, with the intermediate estimate, the true cost of your electricity is about 2½ times as much as you actually pay (because 30 = 2.5 × 12).

The high estimate is about 26 cents per kilowatt-hour, so your price would rise from its original 12 cents to 38 cents per kilowatt-hour, which is more than triple the current price. - Suppose there really was a “coal-powered electricity tax” that made you pay the costs of the externalities. How might that affect the way you use and obtain energy for your home?

Because the price of coal-powered electricity would be so much higher (even with the low estimate), you’d almost certainly try to use less of it. You could do this in at least two general ways. First, you’d probably try to install more energy-efficient appliances, so that your total electricity use would be lower. Second, you’d probably try to obtain energy from other sources. For example, you might install solar panels to generate some or all of your electricity.

Also worth noting: Because all customers would want lower-priced electricity, this tax would also put pressure on the power company to switch from generating electricity with coal to a cleaner source of energy, such as renewables or nuclear.

As you can see from the questions you’ve just answered, the externalities associated with coal are quite substantial. For the context of solving global warming, we need to also consider oil and gas, so economists have tried to come up with overall estimates for the externalities of fossil fuels. Again, there is a large range, but the numbers are always significant. For example, estimates of these “hidden” costs of fossil fuels in the Unites States range from about $300 billion per year to well over $1 trillion per year. Globally, a study by the International Monetary Fund estimated the total costs at more than $5 trillion per year. Future consequences of global warming will make these numbers far higher still.

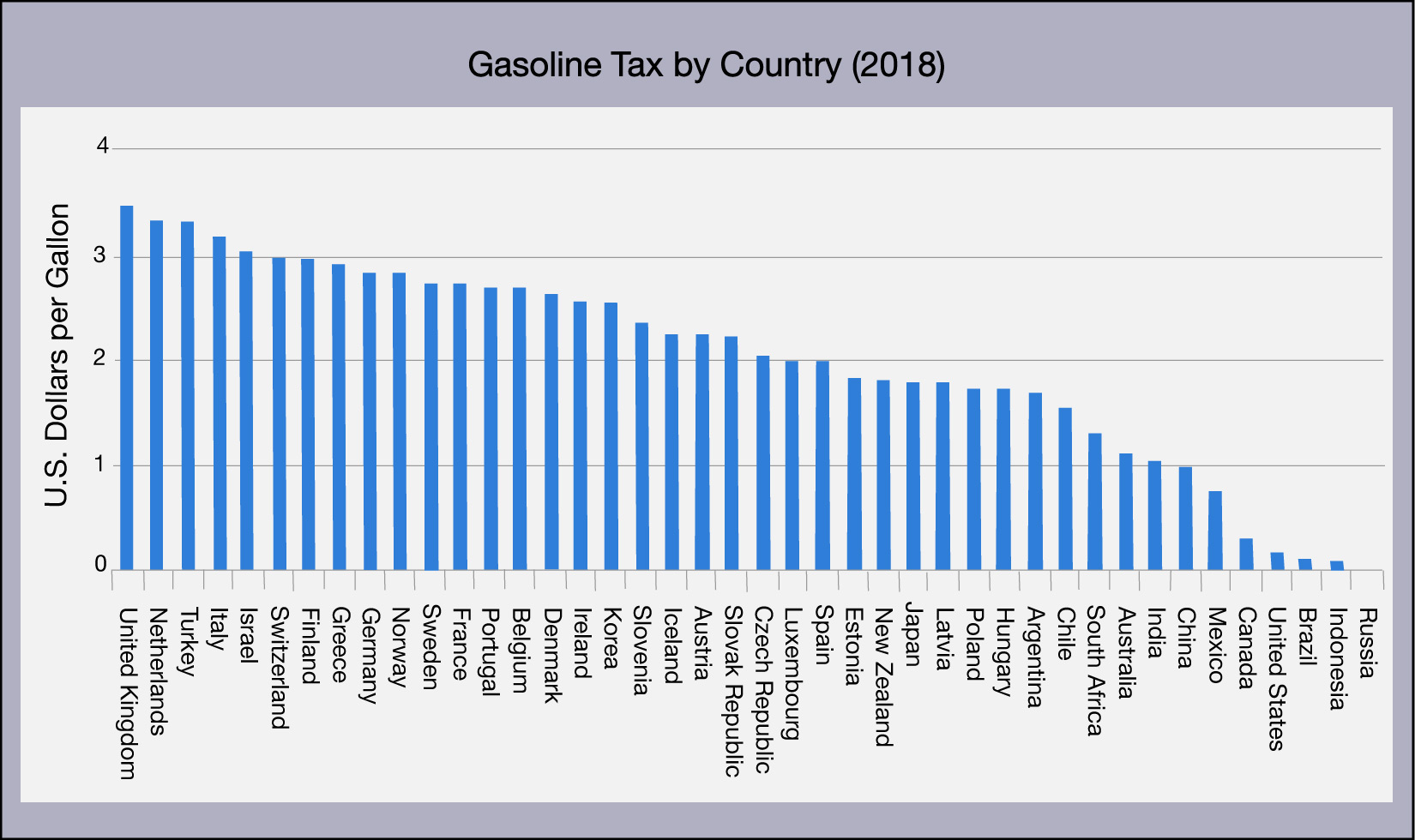

The bottom line is that the true cost of fossil fuels is considerably higher than what we actually pay for them, because current prices generally include only the “up-front” costs of production and transport, not the externalities that are paid later by society as a whole. This suggests at least one way to encourage the use of non-fossil fuel sources: Find some way to build the costs of the externalities into the price you pay when you buy energy, such as by instituting a tax. Most countries already do this for gasoline (Figure 7.3.3–3).

Discussion

U.S./Canada Gasoline Tax Impact

Imagine that the United States and Canada raised their gasoline taxes to match those of the European countries with the highest taxes. What effects do you think that would have on driving and on car purchases? Defend your opinions.

This can be a very brief discussion, with the goal being for students to recognize the behavioral changes that would likely occur with a much higher gasoline tax. Examples of behavioral changes would likely include: driving less to reduce fuel costs; buying more fuel-efficient cars that use less gasoline; speeding the transition to electric cars that don’t require gasoline at all.

Gasoline taxes address fossil fuel use by cars, but of course there are many other uses of fossil fuels. For that reason, economists have proposed a more general way of addressing the externalities of fossil fuels: Institute a carbon tax that would apply to all fossil fuel use. The amount of the tax would be based on how much carbon dioxide (or other greenhouse gas) was emitted into the atmosphere. Because this would make fossil fuels more expensive at the time of purchase, it would make it more likely that people would purchase alternative energy sources, thereby helping to speed the energy transition that we need in order to reduce or stop global warming.

Activity

How Much Do Fossil Fuels Cost?

For this activity, we’ll look at the costs of externalities for fossil fuels in the United States, using the estimated range of about $300 billion to more than $1 trillion per year.

- Using the given range, what is the range in the approximate annual cost per person of the externalities for fossil fuels in the United States?

- Another way to look at the costs is to imagine that they were added to the price of some of our fossil fuel use. Let’s start by looking at doing this solely through a gasoline tax. Drivers in the United States use a total of about 150 billion gallons of gasoline per year. How large of a gasoline tax would be need to account for all of the externalities of fossil fuels? (Give your answer as a range.)

- Perhaps a better way to account for the externalities would be to institute a more general carbon tax , which would be based on how much carbon dioxide an activity emits into the atmosphere. Total U.S. carbon dioxide emissions are approximately 5 billion metric tons (of carbon dioxide) per year. Suppose we instituted a carbon tax that spread the cost of the externalities over all of these emissions. How high would the carbon tax need to be, per metric ton of emissions?

- Do you think that we should have a carbon tax that accounts for the externalities of fossil fuels? Why or why not? Defend your opinion.

This activity is designed to help students think about the costs of externalities associated with fossil fuels. Here, we use U.S. numbers, but if you live in another country, you can feel free to substitute your own country’s numbers.

- (1) Students will need to look up or remember that the U.S. population is around 330 million. So at the low end of the range, the cost per person is about $1,000 (because $300 billion 300 million people = $1,000/person). At the high end, it is more than 3 times as much. So the approximate range is about $1,000 to $3,000 or more per person.

- (2) At the low end of the range, the needed gasoline tax would be $300 billion 150 billion gallons = $2 per gallon. Again, the high end is more than triple that, so the range is about $2 to $6 per gallon.

- (3) At the low end of the range, the needed carbon tax would be $300 billion 5 billion metric tons CO2 = $60 per metric ton of carbon dioxide. At the high end, it would be more than 3 times this, or close to $200 per metric ton. So the range would be about $60 to $200 per metric ton.

- (4) This question leads to the discussion of political solutions that follows, so it is worth first having students think about a carbon tax generally before getting into political specifics.

Discussion

The Morality of Pollution

Both legally and morally, it is fairly obvious that you should not be allowed to dump your trash on your neighbor’s doorstep. Think about this fact as you discuss the following questions.

- Assuming that you are a morally responsible individual, what should you do with your trash? Explain.

- What happens to the trash that your community as a whole generates? Would you say that it is being dealt with in a morally responsible way?

- The use of fossil fuels generates numerous pollutants — and carbon dioxide that causes global warming — that go into our shared air and water. In what way might dealing with these pollutants be thought of as similar to dealing with trash? Explain.

- Do you think our current way of dealing with air and water pollution is morally responsible? Would having a carbon tax change the moral equation? Defend your opinions.

These questions will hopefully generate some interesting discussion about the morality of both trash disposal and pollution. Notes:

- (1) We hope students will conclude that they should (i) minimize the amount of trash they produce and (ii) then dispose of it responsibly. (You might remind them of the mantra “reduce, reuse, recycle”). Of course, this leads to the next question about what happens to the trash after you dispose of it responsibly (such as by having it picked up by a local trash collection service).

- (2) Students may need to do some research to answer this question, which will depend on where you live. Most communities have some sort of communal dump where trash is delivered, but some ship their trash to other, usually poorer, communities. And, of course, some have no enforced rules at all. After students figure out what is happening to their trash, then they should discuss the morality of the current system.

- (3) Just as trash is a by-product of our daily lives, pollution is a by-product of fossil fuel energy. In that sense, we can think of dealing with pollutants as similar to dealing with trash.

- (4) For the first part of the question, we expect that most students will conclude that the current system is not morally responsible, since in most cases we essentially allow the “trash” from fossil fuels to be dumped into our shared air and water. The second part may be more challenging. On the one hand, having users of fossil fuels pay the costs of the externalities would seem to improve the moral equation. On the other hand, it’s still likely to be wealthier people using the fossil fuels that have a disproportionate impact on poorer people, so it raises some of the social justice issues discussed in other parts of this chapter. The key, then, is for students to defend their opinions with clear reasoning.

Political Solutions

We can each do our best to make choices that will help limit global warming, but ultimately, global warming is a global problem, and that means solving it will require global action. But how do we get that to happen?

The short answer is that it takes political action. That is, creating policies that will help encourage the use of technologies that can help us stop global warming. Broadly speaking, we can divide the types of policies that might help stop global warming into two categories:

- Government regulations: These are rules set by local, state, or national governments that are designed to force reductions in greenhouse gas emissions. As an example, consider the fuel efficiency of cars. Because more efficient cars mean lower carbon dioxide emissions, governments can make a rule forcing automobile manufacturers to sell only cars that exceed a certain level of efficiency.

- Economic incentives: Governments can institute fees or taxes (such as a carbon tax) that make the use of fossil fuels more expensive, thereby giving people an incentive to reduce energy use and switch to alternative energy sources. As an example, consider the effects of a gasoline tax. Because the tax makes gasoline more expensive and most people like to save money, this tax provides an incentive for people to purchase more fuel efficient cars or electric cars.

If you look around the world, you’ll find many variations on each of these two basic categories among different local, state, and national governments.

Discussion

Carrot or Stick?

The goal of climate policy is to change people’s behavior in a way that causes the world as a whole to to reduce or end greenhouse gas emissions. Whenever we are trying to change people’s behavior, there are two general approaches, often termed the “carrot” and the “stick.” The carrot approach offers a reward if people make the desired change, while the stick approach means a punishment if they don’t make the change.

- Briefly discuss how the carrot and stick approaches get their names, and how you can use that to remember what they mean.

- We’ve stated that the two basic approaches to climate policy are government regulations and economic incentives. Which of these is more of a “carrot” approach, and which is more of a “stick”? Explain.

- In terms of encouraging more fuel efficient cars, which do you think would be the more effective policy: a regulation requiring high fuel efficiency or a gasoline tax? Explain and defend your opinion.

This is a very brief discussion to get students thinking about the general policy approaches that can modify behavior. Notes:

- (1) While many or most students have probably heard the carrot and stick phrasing before, they may not have ever thought about how they got their names. So it’s worth at least a couple minutes of discussion to make sure they understand that a carrot is a reward that you (or an animal like a rabbit or horse) gets to eat, while a stick implies physical punishment.

- (2) Regulations are essentially a stick approach, while economic incentives are a carrot approach.

- (3) This question is entirely a matter of opinion, so they key lies in how well students explain and defend their options. In case it comes up, you should allow students to choose the option of a combination of both (a gasoline tax and a fuel efficiency standard).

Note: Depending on how much class time you want to spend on this question, you could consider having students divide into teams to make written lists of pros and cons of each approach, and then hold a class debate.

Activity

Your Government Policies

Learn about at least one policy that your local, state, or national government has instituted to try to combat global warming. Prepare either a written a one-page summary or 3-minute oral presentation about the policy and its effectiveness. Be sure to: (1) clearly explain how the policy works, including whether it is a regulation or an economic incentive; (2) briefly discuss what it has accomplished so far; and (3) state and defend your opinion as to whether the policy should be kept as is, strengthened, or replaced with some other policy.

This activity asks students to learn about either a regulation or economic incentive that is used in your area, by either your local, state, or national government. There are probably many policies in place, so you may need to help students choose the ones to research. You should encourage each student or group to research a different policy, so that they’ll see some of the variety of approaches that can be taken.

Regulations and incentives can work at the local state, and national levels, but how do we encourage global action? For that, nations need to come together to make international agreements. Fortunately, this is already being done, primarily through two international groups. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) was created to provide policy makers with the latest scientific information on global warming and its consequences for people around the world. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) organizes discussions and meetings that aim for international agreements on how to deal with the threat of global warming; the “Paris Agreement” that you’ve probably heard about in the news came about through work of the UNFCCC. We won’t discuss these groups in more detail here, but visit their web sites if you are interested in learning more about their work.

Discussion

Carbon Tax and Dividend Plans

As we’ve discussed, one way that governments might incentivize a transition away from greenhouse emissions is by instituting a general carbon tax . Such a tax would have the added advantage of pricing some of the externalities of fossil fuels into their purchase price. However, you are probably also aware that any kind of tax usually generates political controversy. So is there a way to institute a carbon tax that might be acceptable to both conservatives and liberals, as well as everyone else in between? One suggested way of doing this is through what is called a “carbon tax and dividend” (or “carbon fee and dividend”) policy. Three prominent groups (with links to their web sites) advocating this approach are:

Visit the web site of at least one of the above groups and discuss the following questions.

- Looking at the group’s leadership and membership, does the group appear to have a particular political leaning, or does it aim to appeal to people across the political spectrum? Explain.

- What is a carbon “dividend”? Briefly summarize how a carbon tax and dividend plan would work and how proponents believe it would help solve global warming.

- By itself (that is, without the dividends), a carbon tax usually generates opposition from both conservatives and liberals. Conservatives would tend to object to the tax because it would mean more revenue for the government, and conservatives generally favor less government. Liberals tend to object because a carbon tax is like a sales tax in generally having a larger impact on poorer people than on wealthier people. Briefly explain how proponents of carbon dividends believe their plan counters both the conservative and liberal objections. Do you think that these plans really can attract support across the political spectrum? Defend your opinion.

- Another criticism sometimes aimed at these plans is that they only work at a national, not international level, since nations can collect taxes only within their own borders. How do proponents of carbon dividends answer this criticism? Do agree or disagree with their answer? Defend your opinion.

- Hold a full-class discussion about whether you support a carbon tax and dividend plan. If you do, what can you as middle school students do to help put the plan into action (or keep it in action if it has already been adopted)? If you don’t, what type of policy would you prefer?

This activity focuses on carbon tax and dividend plans, and in particular on these plans in the United States, as that is where all three groups (Citizens Climate Lobby, Students for Carbon Dividends, and Climate Leadership Council) are based. In case you are wondering why we have chosen to focus on these as opposed to many other policy ideas, I’ll give you a personal answer as the lead author: I think these plans have the best chance of success of any proposed climate policy plan, both because they generate across-the-political-spectrum support and because I think the market incentives built into these plans would lead to a more rapid revamping of energy use than any regulatory or other approach. That said, I’ve tried to word the question in a way that encourages you and your students both to understand the reasons for my support of these plans and to disagree and suggest alternatives if you wish. Notes:

- (1) All three groups have bipartisan membership and leadership.

- (2) The basic idea is that the revenue collected by the carbon tax would be returned to taxpayers or citizens in the form of dividends. In terms of how it would help with global warming, it is the same answer discussed in the main text: Because the carbon tax makes energy that releases greenhouse gases more expensive, it incentivizes behavioral changes that will lead to using less energy or alternate energy sources.

- (3) The plans answers the conservative objection by returning all the revenue to taxpayers or citizens, so that the government does not end up with more money as a result of the tax. It answers the liberal objection through the fact that everyone receives the same dividend checks. Therefore, since poorer people tend to use less energy than wealthier people, poorer people will on average get dividend checks that are larger than the amount they spent on the carbon tax. In other words, the dividend changes what would otherwise be a regressive tax (in which poorer people pay a higher percentage of income) to a progressive one. (Keep in mind that this progressiveness is an average and there will be some non-wealthy people — especially those who must drive a lot for their jobs — who would suffer under a carbon tax; for this reason, proponents of these plans generally also advocate for government policies to help those who suffer disproportionate impacts.)

The last part of the question is obviously a matter of opinion, but as the membership and leadership of these groups show, these plans have proven to be at least partially successful in appealing across the political spectrum. - (4) There are two basic answers to the criticism that these plans operate only a national level. First, these plans include a “border adjustment” that means imported good will effectively be subject to the tax. Therefore, if countries without a carbon tax want to be able to export to countries with one, they will have to find a way either to implement their own carbon tax or otherwise reduce their greenhouse emissions. Second, these plans are expected to spur innovation in alternative energy, which should ultimately bring down the cost of carbon-free energy sources – and thereby make it more likely that people everywhere will adopt these carbon-free sources, whether or not they have a carbon tax in their own nation.

- (5) This should be an interesting discussion, and to support it, you might wish to introduce alternative ideas. In the United States, for example, you might discuss the proposed “Green New Deal” as an alternate approach, and see which students prefer. Could make for an exciting debate!

Activity

Learn about International Climate Organizations

Visit the web sites of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). You’ll see that each of these organizations has a vast web site with general information, links to reports, news updates, and more. Working individually or in small groups, choose at least one web page that looks particularly interesting to you on one of these two sites. Read it in detail, and then prepare a 1-page summary or 3-minute oral presentation about the organization and what you learned from the web page you chose.

This optional activity gives students the opportunity to learn more about these two organizations (IPCC and UNFCCC) that are frequently in the news. If you assign this project, your goal should be to help students understand why these organizations are considered to be authoritative in their reports and how they are seeking to help spur international understanding of, and action on, climate change.

How Fast Can Change Happen?

The longer we continue to emit greenhouse gases, the worse the problem of global warming will become. This has led many people to urge rapid action, such as eliminating the use of fossil fuels by 2050, or sooner. Is such rapid action realistic?

Remember, the technology to replace fossil fuels already exists. Therefore, the answer to the question of how rapidly we can make the change is really just a matter of how hard we try. For this reason, it’s worth bringing in two historical examples of other times when urgent, large-scale action was need.

For the first, consider the United States in World War II. When the United States entered the war against Nazi Germany, and after being attacked by Japan at Pearl Harbor, the country was just coming out of the worst economic depression in its history. Nevertheless, within a period of only about 3 years, the entire country came together to retool all of American industry — and invented and built new industries — in order to fight the global threats. This example suggests that, if we felt it was important enough, we could similarly retool our energy economy on that type of time scale.

For the second, consider the issue of ozone depletion. As you know from Chapter 6, ozone in Earth’s upper atmosphere protects us from dangerous ultraviolet light from the Sun. In the 1970s, scientists discovered that certain chemicals — especially those know as chlorofluorocarbons, or CFCs, were destroying this ozone. This ozone depletion ( “depletion” means a reduced amount) represented a serious threat not only to human health but also to the health of ecosystems around the world. As a result, the nations of the world came together to sign the global treaty known as the Montreal Protocol (and subsequent revisions to strengthen the treaty). This treaty successfully led to a dramatic decline in the production and use of CFCs, and this in turn allowed the ozone layer to recover.

With these examples in mind, imagine a rapid, global effort to replace existing fossil fuel power plants with either renewable or nuclear power, while also improving energy efficiency and continuing to work on future energy technologies. How rapidly do you think we could put an end to global warming?

Activity

Debate on Urgency

Re-read the quote given earlier from Greta Thunberg, in which she seeks urgent action on global warming. How urgently do you think we need to act, and how rapidly do you think we could realistically put an end to most or all of the emissions that cause global warming? Discuss this question in the form of a class debate:

- Team 1 will argue that the threat is urgent enough that we should commit to using only carbon neutral energy sources by 2050 or sooner. Team 1 should also propose a set of policies for successfully meeting this time frame.

- Team 2 will argue that such a change is unrealistic by 2050, and suggest a longer time frame. Team 2 should also clearly explain why the policies proposed by Team 1 are not realistic.

After the debate concludes, you can disband the teams, and then hold a class vote on which team had the stronger arguments. Can you reach a class consensus on what should be done and how quickly?

For this debate, you can anticipate that most students will prefer the position of Team 1, which is why you should help ensure that Team 2 nevertheless argues as strongly as possible. In particular, be sure that Team 2 comes up with reasonable positions as to why the policies proposed by Team 1 might not work. Still, at the end, we hope the students will vote in favor of urgent action, and come to class consensus on exactly how that action could move forward.

- Be sure that in their arguments, students draw on what they’ve learned in this section, particularly about existing technologies and new technologies that might be available by 2050.

- Also be sure they consider the best ways to achieve urgent action, considering the economic and political realities as well as the scientific and technological ones.