How do scientists measure Earth’s global average temperature?

Excellent question, and the basic answer is “very carefully”! Measuring Earth’s global average temperature essentially requires scientists to average local temperature measurements from many places around Earth, and this is not easy to do. For example, three fairly obvious complexities are:

- Even today, there are large regions of our planet (including the oceans and regions near the poles) where there are no weather stations and no one is measuring temperatures on a regular basis.

- This problem becomes worse as we look to the past, when there were fewer weather stations.

- Many weather stations are located in or near urban areas, which tend to be warmer than they would if the same regions were rural or unpopulated, because urban areas generate their own heat through such means as the absorption of sunlight by pavement and the heat emitted from cars and homes. (This added heat in urban areas is called the “urban heat island effect.”)

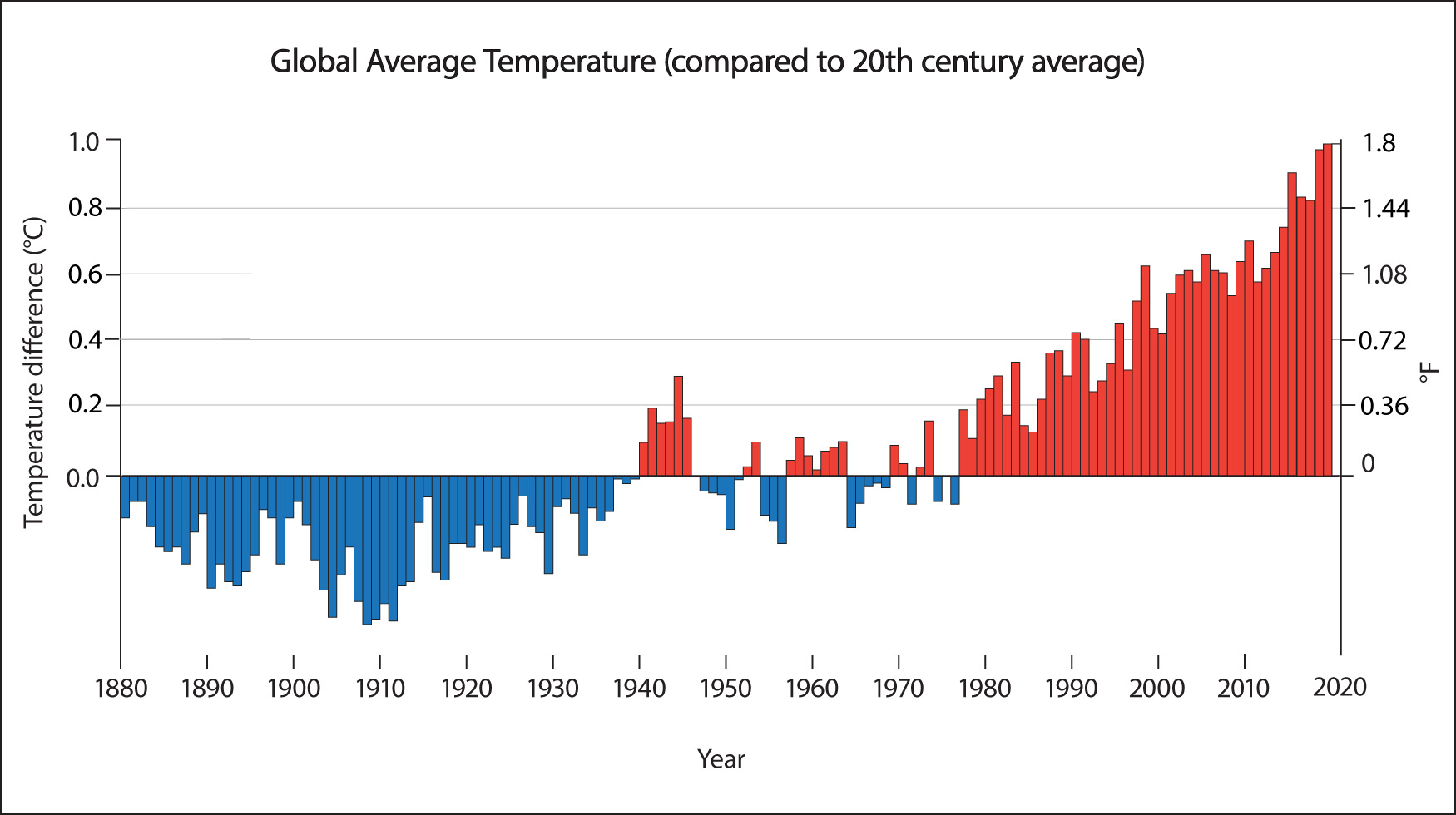

Because of these and other difficulties, there’s always some uncertainty in calculating Earth’s precise global average temperature. In fact, the estimate of 15°C that we used in our “tale of two planets” could be off by as much as a degree or two. That is why Figure 7.1.3–1 shows only temperature differences (scientists often call them “anomalies”) from year to year, rather than actual values.

To understand how this helps, imagine weighing yourself every day on two different scales, one of which always gives you a lower weight than the other. You may not have any way to know which scale is showing your true weight, but if you actually lose five pounds in a week, both scales will probably show the same five-pound loss. In much the same way, year-to-year differences measured by weather stations are much more reliable than their exact temperature readings. Therefore, by averaging year-to-year differences measured at weather stations around the world, scientists can get a reliable record of how Earth’s temperature is changing, even without knowing the “true” average temperature. Moreover, for recent decades, scientists also have data from satellites, which can in effect take measurements from all around the world, including the regions where no weather stations are located.

That said, it’s still not easy. For example, the numbers and locations of weather stations change over time, the heat in cities can change as they grow, and different satellites collect data in different ways. Scientists must be very careful to take these factors into account when computing the change in temperature from one year to the next. Fortunately, several different scientific groups analyze both ground and satellite temperature data, each using somewhat different techniques. The results found by these different groups are all in close agreement, giving scientists great confidence that the warming trend is being accurately measured.

Finally, it’s worth noting that the warming trend shown in Figure 7.1.3–1 probably underestimates the true change. The reason is that, as you saw at the end of video 7–1, polar regions have warmed much more than other parts of the world, but they are underrepresented in the data (because they have relatively few weather stations). Therefore, if we had as many weather stations in polar regions as we do in other places, the data would probably show even greater warming.