Why do you say it will probably never be possible to predict weather more than a couple weeks out?

A century ago, we couldn’t predict the weather well even a day or two ahead of time. Today, weather forecasts are fairly reliable for several days in advance, and most weather web sites will give you a 10-day forecast (though these longer term forecasts often prove to be inaccurate). So you might guess that as our computer models improve in the future, we’ll be able to predict the weather much further into the future. However, there’s a limit to how far out we can expect weather predictions to be accurate, as a result of something that is sometimes called “the butterfly effect.” (Important note: As discussed below, this limitation applies to weather prediction, but not to climate prediction.)

The first step in understanding the butterfly effect is to understand a little bit about how scientists make predictions. In general terms, scientific prediction always requires knowing two things:

(1) the current state, or “initial conditions,” of a system

(2) the laws that govern how the system is changing.

Knowing both things is easy for a simple system, like that of a moving car. For example, if you know where a car is and how fast and in what direction it is traveling, you can predict where it will be a few minutes from now. But prediction is far more difficult for a complex system like weather, which is ultimately created by the motions of countless individual atoms and molecules.

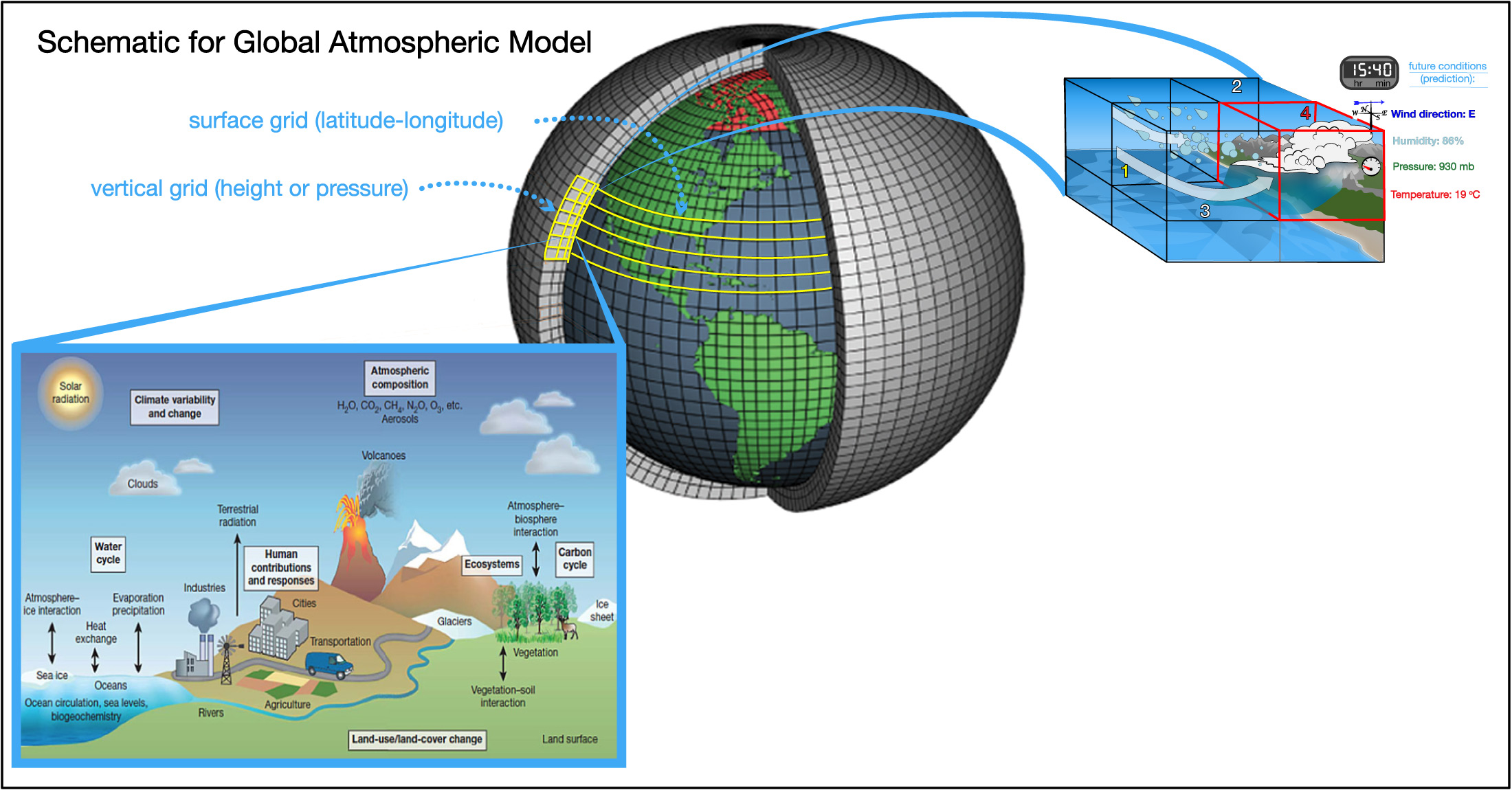

Scientists therefore attempt to predict the weather by creating a “model world.” For example, suppose you overlay a globe of Earth with graph paper and specify the current temperature, pressure, cloud cover, and wind within each square; these are your initial conditions, which you can input into a computer along with a set of equations (physical laws) describing the processes that can change weather from one moment to the next. We’ll discuss such models further in the context of climate in Section 7.2.2, but you can get a quick overview by studying Figure 7.2.2–1, which is shown below.

Once you’ve set up your initial conditions and created your model world, you can use your model to predict the weather for the next month in some particular location, such as New York City. The model might tell you that tomorrow will be warm and sunny, with cooling during the next week and a major storm passing through a month from now.

Now, suppose you run the model again, but you make one small change in the initial conditions, such as a small change in the wind speed somewhere over Brazil. This very slight change in a single initial condition will not affect the weather prediction for tomorrow in New York City at all, and it is unlikely to have any effect on the prediction for next week’s weather either. However, the laws governing weather can cause tiny changes in initial conditions to be greatly magnified over time. As a result, when you compare what your two model runs (your first one and the one with the small change in wind over Brazil) predict for New York’s weather a month from now, you may find the two predictions to be very different; for example, one model might predict cold and rain a month from now, while the other predicts warm and sunny.

The fact that tiny changes in initial conditions can lead to huge changes in predictions a month later explains why weather models can never be reliable more than a few weeks out. In essence, the problem is that we’ll never be able to know the initial conditions perfectly enough to make reliable predictions for, say, a month in the future. That is why the problem is called the “butterfly effect”: If initial conditions change by as much as the flap of a butterfly’s wings in one part of the world, the resulting long-term predictions may be very different even for far-away places in the world.

Keep in mind that the fact that weather predictions become unreliable does not mean that climate predictions will have the same problem. The reason is that even though the butterfly effect may make a prediction for a particular time and place (such as New York City in one month) unreliable, it will not affect predictions for the average weather that a region would experience over many years. That is why climate prediction is actually much easier and more reliable than weather prediction .