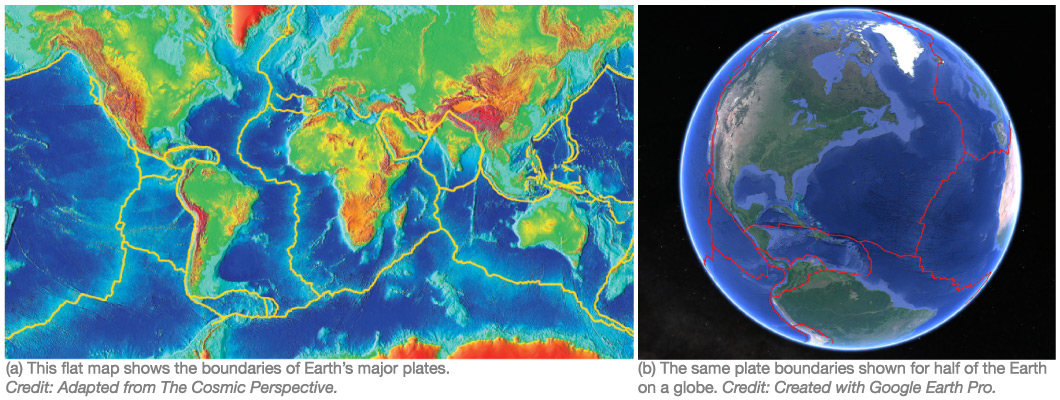

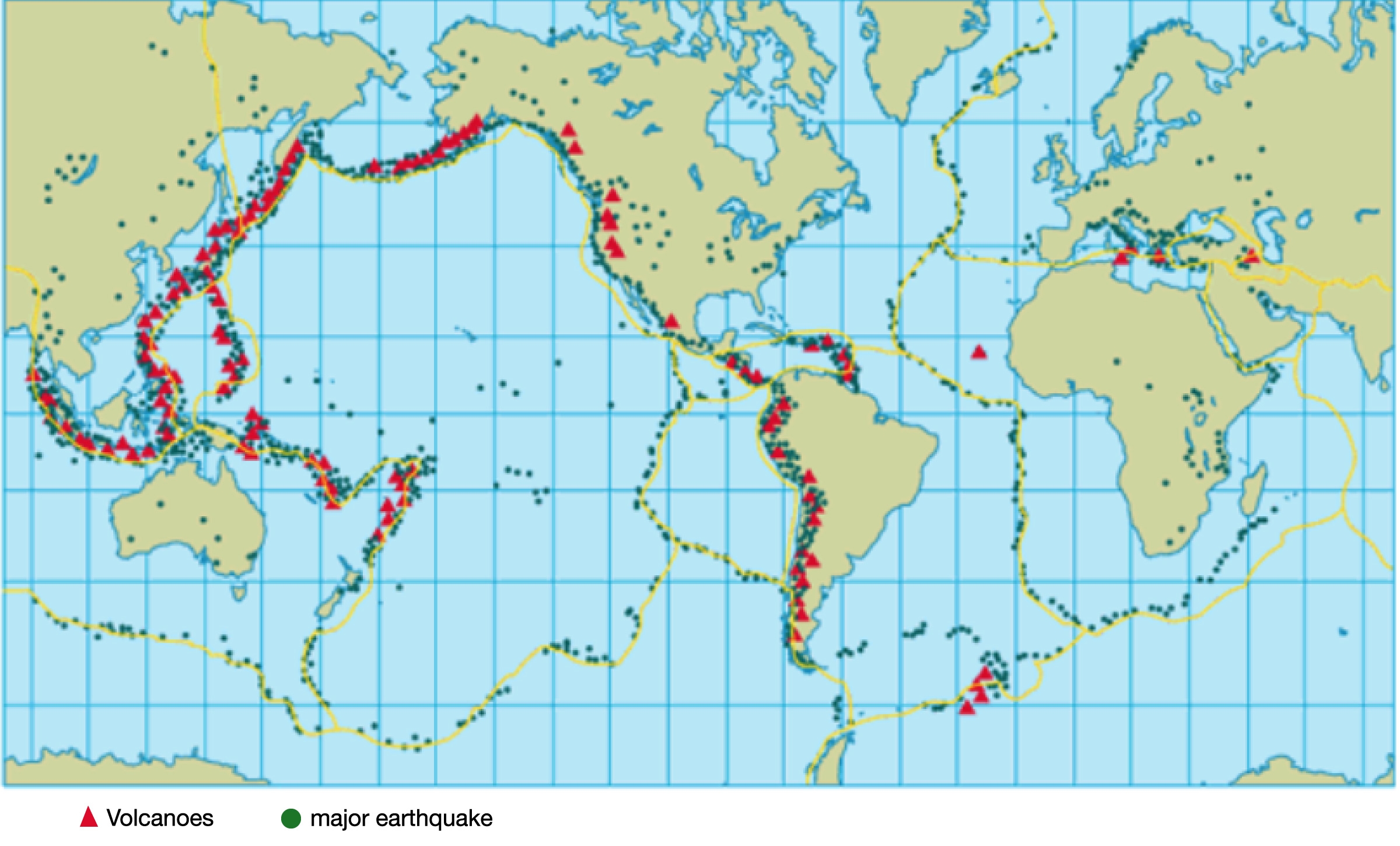

Take a look at the distribution of earthquakes and volcanic eruptions on the map in Figure 5.3–1. It’s immediately obvious that the distribution is not random. Instead, the distribution divides up the globe with a set of borders in much the same way that we humans divide up the land with national borders. But what exactly are these borders?

The answer will become clear if you look at the yellow lines on the map: The earthquakes and volcanoes are tracing the outlines of Earth’s tectonic plates (which we first showed in Figure 4.19). In fact, the mapping of earthquakes and volcanoes is one of the main ways in which scientists have learned where plate boundaries are located.

We’ve already discussed some of the reasons why earthquakes and volcanoes occur along plate boundaries. We’ve also already introduced the basic idea of plate tectonics, in which we understand Earth’s geology through the motions of the plates. In this section, we’ll build on our prior discussion to put together a fuller picture of how the scientific theory of plate tectonics explains nearly all the major features of Earth’s geology. We’ll also explore how scientists first figured out that the plates exist.

Section Learning Goals

By the end of this section, you should be able to give general answers to the following questions:

- What evidence led to the idea that continents move?

- How does the theory of plate tectonics explain Earth’s major features?

Before you continue, take a few minutes to discuss the above Learning Goal questions in small groups or as a class. For example, you might discuss what (if anything) you already know about the answers to these questions; what you think you’ll need to learn in order to be able to answer the questions; and whether there are any aspects of the questions, or other related questions, that you are particularly interested in.

Connections—Etymology

Tectonics

Think about the term plate tectonics. The “plate” part should make sense, since the boundaries of Earth’s plates do indeed make the crust look somewhat like a broken plate. The second part of the term, “tectonics,” comes from the Greek word tekton, which means “builder.” Therefore, tectonics is essentially the process of building something, and in geology it refers to the “building” of geological features by stretching, compression, or other forces acting on a world’s surface. Plate tectonics refers more specifically to the “building” processes that we can trace to the fact that Earth’s surface is broken up into plates.

You’ll note that the same root — tekton (meaning “builder”) — occurs in a few other familiar words. For example, the word architect means “master builder.” Moreover, it is closely related to another Greek word, teknikos, which pertains to art or craft in work. With that in mind, you’ll see that there is also a close connection between the word tectonics and words such as technology, technical, technique, and more.

Group Discussion

Concepts of Plate Tectonics

In small groups or as a class, briefly discuss the following questions. You may not yet know all the answers, but you will learn them by the end of this section.

- Look back at Figure 4.19 and identify the plate that you live on. Where are its boundaries? Bonus: Find out the name of the plate you live on.

- If you think back to our discussions earlier in this chapter, you’ll realize there are three general ways in which plates can move relative to one another at plate boundaries. What are they? What names would you give to these different types of plate boundary.

- As we’ll soon discuss, the idea of plate tectonics grew out of an earlier idea called “continental drift.” Looking at a globe, do you see anything that might make you think the continents have drifted over time?

- The subtitle of this section calls plate tectonics the “unifying theory of Earth’s geology.” What do you think that means? Do you think that plate tectonics qualifies as a true scientific theory , as defined in Chapter 3?

This discussion is intended to help students think about ideas of plate tectonics before we discuss the details, in hopes that they will be more motivated to learn the material. As usual for these diagnostic questions, you should not necessarily expect student to know the answers at this point, only to give thoughtful responses. Notes:

- (1) Finding your plate should be fairly easy by studying the plate map. Note that names of plates were given previously in Figure 5.2.1–3a, or students can look up plate names on the web.

- (2) Students have already seen examples of all three basic types of relative plate motion, which are colliding (called a convergent plate boundary), pulling apart (called a divergent or rift boundary), and moving sideways (called a side-slip or transform boundary).

- (3) Students may already have heard of and therefore recognize the “fit” of South America and Africa, and perhaps other fits as well.

- (4) Here, we hope students will already recognize how the ideas of plate tectonics successfully explain many features of Earth that we’ve already discussed, and also recognize that it qualifies as a scientific theory because of the abundant evidence that supports it, including (as we’ll discuss) direct measurements of plate motions with GPS technology.

Optional Video

New Perspectives on Humans and the Earth

Watch the episode “The Lost Worlds of Planet Earth” of the Neil deGrasse Tyson series “Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey” (available on various streaming services). After watching the video, hold a brief class discussion about how what you have learned changes your perspective on Earth’s history and the human race.

This outstanding episode of Neil deGrasse Tyson’s series can serve as a great introduction to this section, as it discusses how we discovered plate tectonics. It also discusses the end-Permian and other mass extinction events. The goal of the discussion is for students to consider how these ideas might change their perspective on our place in the world. Note: While we recommend using this video as an introduction and motivation for the details that following this section, you could alternatively use it as a summary at the end of this section.